SLAC

Student Labor Action Coalition

Madison, WI

The Sweat-Free Campus Campaign

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ) for the University Community

On September 28, 2005, United Students Against Sweatshops unveiled a proposal to improve the way in which colleges and universities enforce their anti-sweatshop policies. We recognize that members of the campus community may have questions regarding the meaning of different elements of the proposal and their implementation. This document seeks to address a number of potential questions, including:

- 1) Why is the Sweat-Free Campus Campaign necessary?

- 2) What are we proposing?

- 3) Are there enough factories that meet these standards to supply the university market?

- 4) Won't concentrating university apparel into a smaller number of factories decrease our impact on the industry at large?

- 5) Won't consolidating university apparel in a smaller number of factories cause job loss?

- 6) Won't increasing wages lead to higher retail prices?

- 7) Won't increasing wages lead to a loss of jobs?

- 8) Isn't it difficult to determine a living wage?

- 9) Isn't it difficult to ensure that brands pay sufficient prices to their suppliers?

- 10) Why must designated factories produce primarily or exclusively for the university market (or for other brands committed to equivalent standards)?

- 11) Will this proposal help workers win improvements in benefits and other areas besides wages?

- 12) Why do workers need a union or another representative organization for a factory to be good?

- 13) Isn't it difficult to determine whether a union or other worker organization is legitimate?

- 14) Will smaller licensees or companies that make specialty products have difficulty with the new requirement?

- 15) Wouldn't the proposed policy amount to just the type of "certification" program, carried out by organizations like the Fair Labor Association, that USAS has long opposed?

- 16) How do you know that my campus' apparel is still being made in sweatshops?

- 17) Aren't some elements of the proposed policy illegal?

1) Why is the Designated Suppliers Program necessary?

United Students Against Sweatshops was created to ensure that all workers making university apparel have dignified working conditions. Universities have been able to use codes of conduct successfully to support workers' efforts to achieve positive change in individual factories. But while we are very proud of these achievements, we also recognize that not nearly enough has changed in factories producing collegiate apparel. Apparel workers around the world too often face abusive treatment, excessive working hours, wages that are woefully inadequate to meet basic needs, unsafe and/or unhealthy working conditions, and the denial of universally acknowledged associational rights when they attempt to press for improvements. Apparel brands put tremendous pressure on their supplier factories to cut costs and these pressures make broad, deep and sustainable improvements in wages and working conditions effectively impossible. The gains we have seen at individual factories have been too limited and too fragile.In short, large obstacles stand in the way of meaningful improvements in factory sites. In order to bring us to the day when students and others can purchase collegiate apparel knowing that these items are produced under dignified working conditions, we need stronger tools than current codes of conduct and code of conduct enforcement strategies provide. After extensive consultation with worker rights advocates and with experts on the apparel industry - in the U.S. and abroad - we have developed a proposal for a new approach to campus code of conduct enforcement. We call it the Designated Suppliers Program.

Our campaign proposes that university apparel be made in a set of designated sweat-free factories in which workers are able to enforce their rights through unionization and earn a living wage. Brands that are licensed to make university apparel would be required to produce these garments in factories that meet the following criteria, as verified by the Worker Rights Consortium:

- The factories must demonstrate full respect for the worker rights standards in university codes of conduct.

- The factories' employees must be represented by a legitimate, representative labor union or other representative employee body.

- The factories, once they are receiving prices sufficient to make this feasible, must demonstrate that their employees are paid a living wage.

- The factories must produce primarily or exclusively for the university market, or for other buyers committed to equivalent standards (including payment of a living wage).

The meaning of these standards is discussed in this document, as well as in the Designated Supplier Program proposal. The requirement on licensees to source from factories that meet these standards will be phased-in over time; in the first year 25% of products must come from designated factories, with this number rising to 75% after three years as more factories are brought into this system.

3) Are there enough factories that meet these standards to supply the university market?

It is currently not possible for apparel factories around the world, particularly in developing countries, to meet all of the standards required in this program, including the payment of a living wage. This is because the prices that brands are willing to pay factories for goods are simply too low to enable a living wage to be paid - let alone for all other code of conduct standards to be fully respected. However, we are very confident that more than a sufficient number of factories could quickly achieve the standards of this program once it is implemented. Indeed, given the current crisis in the global apparel industry - in which factories in many countries are truly desperate for orders - there are surely more than enough factories that would be willing to offer superior labor standards in exchange for guaranteed access to steady orders at reasonable prices. When asked, some factory managers have privately expressed support for the idea.

There are, in fact, a large number of apparel factories around the world that already partially fulfill these standards, having recognized legitimate unions or other representative worker bodies. The WRC will provide a list of factories that have met this criterion and that could likely qualify with the rest of the standards if the program were implemented and steady orders at reasonable prices were provided. Licensees will be able to select factories from this list.

Universities and brands may be legitimately concerned that the factories that are currently unionized or have representative worker bodies do not produce the exact type of goods they sell at the quality or quantity they require. If licensees prefer, as we expect some will, they can work to bring factories in their existing supplier networks up to the program's standards. The WRC would assist in this process by helping to develop plans for what specific steps facilities must take in order to comply with the program (e.g. by demonstrating full respect for workers' associational rights and paying a living wage). The WRC would also recommend factories as candidates for the program where positive efforts by workers to establish representative employee bodies are underway. Note that factories will only ultimately qualify as designated suppliers if workers freely choose to associate in a union or another representative body, such as a cooperative. Great care will be taken to ensure no facilities with illegitimate unions are included. It is important to emphasize that since brands are welcome to bring their existing factories into the program, there is no basis for concerns that there will not be a sufficient number of factories capable of producing the necessary products with adequate quality.

4) Won't concentrating university apparel into a smaller number of factories decrease our impact on the industry at large?

The proposal will strengthen our positive impact on the industry at large by significantly raising standards in factories that can then become the baseline for the broader industry. Universities can take the lead in demonstrating to consumers, workers, and others that it is possible to manufacture clothing under sweat-free conditions.

The truth is, while collegiate apparel is currently produced in thousands of factories around the world, this does not translate into a situation in which we can help workers in each of these factories make improvements. The dispersion of university production across so many factories substantially undermines the ability of universities to have a positive impact on working conditions. First, this reality makes effective across-the-board monitoring on an on-going basis virtually impossible. Second, university apparel typically makes up only a small fraction (generally well under 5% annually) of the apparel produced in a given factory; the rest of the factory's production is usually for big box retailers like Wal-Mart and Target, and major brands like Nike, Reebok, the Gap and others. As a result, the leverage university licensees bring to factories - even when a licensee wants to press a factory hard - is often too little to make a difference. Universities are ultimately forced to rely on the good will or vulnerability of whatever non-collegiate brands are in the factory to press for improvements, brands that are not in any way accountable to universities. If these companies are not responsive, as many are not (e.g. Wal-Mart, J.C. Penney, etc), there is little that universities or their enforcement agents can do to press for meaningful change. The result is that violations of worker rights continue to be rampant in factories producing university apparel. And as mentioned earlier, when workers in alliance with universities succeed in making improvements at these factories, these changes are usually limited and fragile because there is no commitment on the part of any of the brands to sustain these improvements by continuing to order goods from the factories and pay a price sufficient to make sustainable improvements feasible.

How would the new proposal strengthen our ability to make change in the industry at large? In all factories where collegiate apparel is made, we will be able to directly support the rights of workers. There are two key ways in which this can happen. First, we can demonstrate that a higher standard is possible in the apparel industry - a standard that non-collegiate brands can then be held to. If universities succeeded in helping to establish a set of factories that were truly decent places to work - factories that adhere to a higher standard than the unacceptable industry norm - it would be difficult for non-collegiate brands concerned about their public images to justify maintaining the status quo. Second, the new program will help enable positive change in specific factories that are not currently producing collegiate apparel. The new program will establish a market that rewards factories that fully respect worker rights with stable orders at sufficient prices. This will create a positive incentive for factories to stand-out for their respect of worker rights, something which currently does not exist in the apparel industry. Workers at individual factories pressing for improvements can use the program as a carrot, by credibly indicating to management there are economic rewards for high labor standards.

By demonstrating that a truly decent standard is possible and by providing positive incentives for factories to fully respect worker rights, the new program will strengthen our ability to positively impact the industry at large.

5) Won't consolidating university apparel in a smaller number of factories cause job loss?

There is little reason to expect that any significant job loss at particular factories beyond that which is already occurring would result from consolidating university production in a smaller number of factories. The program will create far more stable employment for apparel workers.

It is important to understand that, at present, the apparel industry is dominated by extreme instability and volatility, with brands constantly shifting business from factory to factory in search of the cheapest price - causing frequent factory closures and a chronic lack of job security for workers. This sort of constant shifting of orders takes place among university licensees, so that there is little year-to-year or even month-to-month consistency in the thousands of factories that licensees use to produce logo goods. Since collegiate apparel currently represents a tiny portion of each factory's annual production (as just noted, usually well under 5%, with the rest of a typical factory's production occurring for big box retailers like Wal-Mart and Target), the one-time consolidation of university production into designated supplier factories would likely entail less redistribution of orders than is already occurring on an ongoing basis. In other words, some very small amount of job loss might result from implementation of the program. Yet, compared with the current situation of constantly shifting production and chronic job insecurity for workers, the shift in production that would result from this program would have little observable effect on production levels or workforce levels at factory sites from which production is shifted.

What the new program will enable, for the first time, is real, long-term stability for a substantial number of factories and their employees. Under the designated supplier program, the chaotic system of constantly shifting orders will be replaced with a structured, rational system that offers real job security for workers.

6) Won't increasing wages lead to higher retail prices?

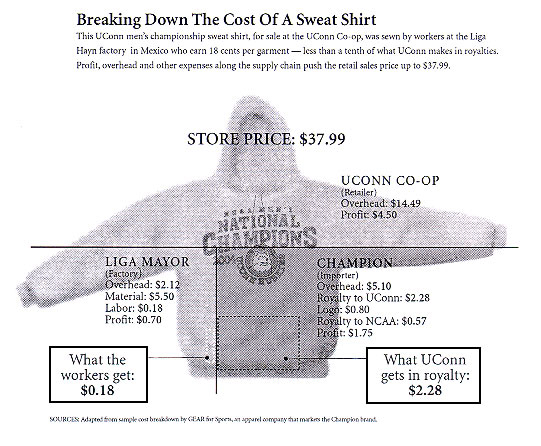

The economics of the industry are such that workers' wages could be raised by very substantial margins without large increases to retail prices. This is primarily because labor costs account for such a small portion of a product's total price: usually about 1-3% of the final retail price for garments produced in developing countries. For example, for a shirt sold on campus for $20.00, workers are typically paid about 25 cents. Even if the entire cost of wage increases is passed directly on to consumers, wages could be doubled and the shirt's retail price would only increase to $20.25. There is no reason to doubt that consumers would be willing to pay these nominal cost increases when they buy campus apparel products, which already have enormous cost mark-ups. If brands decide to absorb some of the increased costs, then price increases would be that much smaller. (The appendix to this document provides a breakdown of the costs of manufacturing and selling campus apparel, published by the Hartford Courant.)

Indeed, there is already more than enough money in the system for brands to pay higher wages. Nike's annual advertising budget is $1.4 billion dollars. Less than 1% of this amount would be needed to double the wages of all of Nike's collegiate apparel workers.

7) Won't increasing wages lead to a loss of jobs?

This claim is based on the premise that brands would be forced to make fewer products, since consumers would not be willing to pay the higher prices that would result from wage increases. The claim makes little sense in the university context. There is no reason to expect that the proposal will have any observable effect on the overall amount of campus apparel that is sold. As discussed above, because labor is such a small portion of overall costs, large wage increases (resulting in double or triple current wage levels) would require only very small increases in retail costs, if brands choose to pass on the costs to consumers instead of absorbing the modest increases themselves. The collegiate apparel market is characterized by enormous mark-ups already: for example, the price of a sweatshirt with a university logo is often 150% of the price of the exact same sweatshirt without the logo. Since consumers are not buying collegiate apparel because of low prices, there is no reason to believe they will buy less of it if the price increases by one or two cents on the dollar.

It is also important to note that the requirement on licensees to pay fair prices to their suppliers would be imposed across-the-board on all licensees. Since every company will be required to adhere to the standard, no company will be placed at a competitive disadvantage for paying fair wages and having modestly higher prices. There are all kinds of factors affecting the apparel industry at large which cause minor fluctuations in the overall costs of making and distributing apparel - such as changes in the cost of electricity and fuel, etc. - but which have no observable effect on total apparel sales. Since there is no reason to expect that overall sales will decrease, there is no reason to conclude that any job loss would result.

8) Isn't it difficult to determine a living wage?

The primary strategy of many brands opposed to paying a living wage has been to claim it is a tremendously technical issue, too complex and too thorny, to figure out. Of course, this is an ironic position to be taken by multinational companies that have developed cutting edge supply networks for manufacturing clothing in the farthest corners of the globe. But this strategy has been successful in stalling meaningful progress on living wages.

The reality is that determining a living wage is a fairly simple task. It amounts to determining the cost of a basic basket of goods and services that workers and their families need for a decent standard of living in the region where they live. A basic market basket includes: nutrition, potable water, housing, energy, transportation, healthcare, childcare, education and savings. This is not rocket science to measure. Our solution is to simply commission local people with expertise on this subject to gather data on the cost of the market basket in the region in question and then calculate, transparently, the total amount of local currency that is necessary for a worker and family members who are dependent on her income to afford these items. This exercise has already been carried out successfully in various countries, generally finding that current wages are between one half and one fourth of what a worker and her dependents need. The Worker Rights Consortium has agreed to calculate sample living wage figures for the university community as the new proposal is being considered. These figures will serve to both dispel the myth that calculating a living wage is a daunting task, and also to give a sense of the kind of wage increases that will be necessary to achieve living wages.

Because wage and compensation issues are best addressed through negotiation between worker representatives and employers, the implementation of the living wage at the factory level will take place through collective contract negotiations, supported by a complaint process if necessary. The WRC will respond to complaints regarding the alleged failure of supplier factories to pay a living wage. On the basis of an assessment by a team of experts regarding the cost of the basic basket of goods in the region, the WRC will make a determination as to whether the factory is in compliance or non-compliance with the living wage standard. If the factory is found in non-compliance, and it fails to address the issue adequately, the factory would lose its status as a designated university supplier.

9) Isn't it difficult to ensure that brands pay sufficient prices to their suppliers?

One aspect of the enforcement of this policy requires ensuring that licensees pay prices to factories that are sufficient for the factory to comply with each of the program's standards. In practice, universities will not need to become involved in the negotiation of each apparel contract. Rather, the licensees and factories will negotiate the terms of contracting agreements on their own to determine an appropriate place. The WRC would ensure that the prices paid are sufficient through a combination of spot checking and assessments triggered by complaints where disputes have arisen.

There are strong precedents for enforcement of a fair pricing standard. California law provides one example. The California Labor Code (Section 2673.5) requires apparel companies to ensure that the prices they pay to contractors are sufficient to enable compliance with labor laws. The law holds companies accountable as guarantors for unpaid wages owed to workers by contracted supplier factories if the companies have engaged in "Š unreasonably reducing payment to its contractor where it is established that the guarantor knew or reasonably should have known that the price set for the work was insufficient to cover the minimum wage and overtime pay owed by the contractor." This legislation was enacted precisely out of concern that inadequate prices paid by brands to factories are frequently the driving force behind widespread violations of minimum wage and overtime laws. The Labor Commissioner has the authority to mediate disputes regarding pricing issues and defer disputes to arbitration or to the court system.

Similarly, the U.S. Department of Labor (DOL) has required apparel companies participating in a DOL-sponsored factory monitoring program to adhere to a fair pricing standard. The agreement underlying the program, the Augmented Compliance Program Agreement (ACPA), requires apparel companies to perform an evaluation before each apparel purchase to ensure the "economic feasibility of the price terms that are involved, in light of the compliance with the [Fair Labor Standards Act] and the [Employer Compliance Program] required of the Contractor and in light of the calculations and expectations of the parties to the purchase." An analysis of the DOL's program found that ability of supplier factories to renegotiate contracts with buyers when conditions change was the single most powerful predictor of a factory's compliance with minimum wage and overtime laws, more powerful even than whether the factory has been "effectively monitored" by compliance agents.

We have consulted with experts, including current and former government officials responsible for labor standards enforcement in the apparel sector, who have consistently agreed that the exercise of determining whether a price paid to an apparel contract is sufficient to enable compliance with labor standards is entirely doable, assuming that the factory is willing to make production data available to inspectors. In enforcing this standard - which, as noted, will occur only when concerns arise about the prices being paid - the WRC would commission a team of trained specialists with expertise on production costs in the apparel industry. The team would assess the factory's production costs for the product in question and make a determination as to whether the prices paid by the licensee to the factory for the logo products is sufficient to enable full compliance with the program's standards.

10) Why must designated factories produce primarily or exclusively for the university market (or for other buyers committed to equivalent standards, including payment of a living wage)?

This is requirement is essential for the program to work. Factories must have orders in sufficient quantities if they are going to be able to fully adhere to program's standards, including payment of a living wage. It is clear, for example, that if a factory is receiving a price for orders commensurate with the costs of paying a living wage for only 10% of its garments, the factory will simply not be able to afford to pay a living wage to 100% of its workers. Similarly, we cannot count on factories to provide steady employment and job security for all workers if only a minority of their customers are committed to providing stable, long-term orders. Moreover, generally speaking, without access to a guaranteed market of committed brands, factories will not have a compelling incentive to take part in the program and thereby take on the extra costs required to provide exemplary labor standards - costs which would otherwise make them uncompetitive with factories that have lower standards. Universities must have a way of channeling substantial, steady business to factories willing to take on the costs of complying with university standards. We believe this is best accomplished through the proposed policy. The other option we have entertained to channel orders to these factories and prevent the excessive dispersion orders would be to limit the size of the list of eligible factories. However, this approach does not seem workable, as it would require a constant and tedious matching of overall supply with demand and would limit the program's flexibility to bring factories from brands' existing networks into the fold. For these reasons, the Designated Supplier Program requires that licensees ensure that those factories they intend to use toward fulfillment of their obligation under the program have sufficient orders to ensure that two thirds of annual sales are for the university logo goods market or for other buyers committed to equivalent standards (including payment of a living wage).

11) Will this proposal help workers win improvements in benefits and other areas besides wages?

If there appears to be a large focus on wages in discussions about the new proposal, it is simply because it is a "big ticket" item and it raises immediate questions about whether the proposal is economically viable. It is also a key area in which garment workers and their advocates have made little or no gains to date. But wages are only one part of the aims of this program. The goal is for workers to be able to win dignified working conditions in all aspects of employment, including working hours, health and safety, benefits, and other areas. The factories that will end up producing campus apparel will need to meet a comprehensive set of standards - including each standard included in our universities' codes of conduct, and the prices paid by brands will need to be sufficient for the factory to comply with these standards. Workers in each of these factories will be represented by a union or another organization and will address the issues of most importance to them through direct negotiations with factory management.

12) Why do workers need a union or another representative organization such as a cooperative for a factory to be good?

As a practical matter, there is no way for an outside organization to know workers' rights are being respected on a daily basis in apparel factories overseas, unless workers have a sustainable way to prevent abuses and advocate for their interests. Workers are the best monitors of their working conditions. Unlike outside auditors - which may visit a factory once every several months or years - workers are on the shop floor day-in and day-out and they know better than anyone else what problems exist. When workers have a voice on the job through a union or another representative organization, they have the power to advocate for their interests and correct abuses when they occur, without being forced to rely exclusively on outside entities. Without workers having the capacity to advocate for their own interests, there is no way to ensure that workers' rights are being respected. The combination of independent unions and independent monitoring will ensure that workers' rights are respected in all Designated Supplier factories.

Moreover, given the realities of the global apparel industry, it is impossible to be sure that the specific right of workers to associate freely - a right guaranteed by all codes of conduct - is being respected if workers are not represented by a union or other representative worker organization. From Bangladesh to Mexico to El Salvador, violations of the rights of workers to collectively press for improvements is so pervasive in the apparel industry as to be the rule, rather than the exception: in most factories in most apparel producing countries, workers have been convinced that if they choose to organize for improvements, they will be fired, demoted, and/or they will not be able to find work elsewhere. Apparel brands have contributed to this situation by turning a blind eye to routine violations over a period of years and by refraining from pressing factories to take actions that would meaningfully address the problem. Given these realities, there is simply no way to have any certainty that associational rights are being meaningfully respected unless a factory has proactively demonstrated its commitments to worker rights in this area by engaging in good faith with an organization that represents workers.

It is important to note that the critical issue here is not that workers have unions per se, but that they are genuinely empowered to enforce their rights on an ongoing basis. The program's standards would enable a range of different types of workplaces to be included. In countries such as China where the law formally prohibits the free association and collective bargaining of workers, if factories nevertheless demonstrate that, in practical terms, workers are able to join together and freely negotiate the terms of their employment and address grievances with management, and the factories meets all other standards of the program, we see no reason why such factories should be excluded. (Bringing factories to this point will no doubt require more aggressive actions by brands than they have thus far been willing to take, but we believe it is possible.) In addition to traditional factories, cooperative workplaces, in which workers have meaningful representation in decision making bodies and a means of addressing grievances, would also be included.

Finally, we want to emphasize that the aim of this campaign is not "protectionist" in any way, as some may inaccurately assume. Our goal is for factories included in this program to come from a wide range of countries in all regions of the globe.

13) Isn't it difficult to determine whether a union or other worker organization is legitimate?

We do not believe this is a prohibitively difficult task. Indeed, during the past five years, the WRC has routinely done so in carrying out its assessments of individual factories. Factory reports are available online at www.workersrights.org. To our knowledge, in no case has the WRC's conclusion been seriously questioned. The process of determining whether a union or another organization is a legitimate representative of workers rests largely on a handful of questions. Has the organization demonstrated that it has been meaningfully elected and fulfilled other legal requirements to represent workers? Has the organization fought vigorously for the rights and interests of workers? These questions are answerable through factory level research and consultation with local experts and, once resolved, settle the great majority of questionable cases. Instances in which unions have been installed by management would be identified and disallowed. For the purposes of the designated suppliers program, we propose that this process be undertaken by the WRC, which would make a determination based on its own research and on consultation with relevant experts in this area.

14) Will smaller licensees or companies that make specialty products have difficulty with the new requirement?

As currently written, the policy only applies to licensees producing apparel and other textile products (backpacks, flags, etc), so companies selling highly specialized products such as university-inspired birdhouses or helmet-shaped chocolate would not be affected at this point. While it is certainly true that large companies like Nike are more able to absorb the tiny cost increases necessitated by the payment of a living wage, this increase is such a small percentage of the retail cost of a garment (1-3%) that there is no reason to believe that it will place an insurmountable burden on small licensees or local retailers of collegiate products. Furthermore, this requirement is being imposed on apparel licensees across-the-board: no one company will be placed at a competitive disadvantage because everyone will be required to pay the slightly increased prices for products from the good factories.

15) Wouldn't the proposed policy amount to just the type of "certification" program, carried out by organizations like the Fair Labor Association, that USAS has long opposed?

To answer this question, it is important to first understand why USAS and the anti-sweatshop movement opposes existing certification schemes (including both those that certify brands, like that of the Fair Labor Association, and those that certify factories, like that of Social Accountability International and the Worldwide Responsible Apparel Program). None of the current "certification" programs - FLA, SAI, or WRAP - are regarded as credible by the mainstream anti-sweatshop movement - not because there is something wrong with directing business to factories that fully respect worker rights, but because none of these organizations actually do so.

First, under these programs, the "certification" process is controlled by multinational apparel companies or organizations funded and controlled by them. Our program does not let the industry define for itself whether a factory has made the grade - an approach that has failed miserably to curb sweatshop abuses. Instead, under our proposal, the program will be overseen by an organization that is truly independent of the apparel industry, has the trust of workers, and has a proven track-record of firmly insisting on full respect for worker rights - the Worker Rights Consortium. Factories will only be included if they are recommended by workers and worker allied organizations with accurate, ongoing knowledge of working conditions.

Second, each of the existing certification programs place a stamp of approval on working conditions without any reasonable assurance that the conditions are in fact decent. In each of the programs, the certification is based on corporate-sponsored monitors visiting a sampling of factories once per year, or in the FLA's program once per decade - a process that has proven woefully ineffective at ensuring that conditions are truly decent. Instead of relying on sporadic visits by corporate monitors to check on conditions, under the designated suppliers program there will be ongoing monitoring and enforcement of rights by workers themselves through their unions or other representative organizations, supported by a strong and proven complaint process, backed up by independent verification.

Third, under the current certification schemes, the standards against which factories are held are themselves inadequate. Most notably, there is no requirement that a living wage be paid. Instead of relying on absurdly low minimum wage laws (which are themselves frequently not enforced), this program sets a decent standard - a living wage - to ensure workers and their dependents are able to make ends meet.

Fourth, under current certification schemes, no requirements are placed on brands to ensure it is possible for their supplier factories to offer decent conditions. Instead of pretending as though it is possible for factories to offer truly decent conditions while they are at the same time competing desperately for orders, in a buyer's market, from brands intent on low-balling them, this program ensures it is possible for factories to offer stable, sweatshop-free employment. The program will establish university supplier factories, protected from the downward pressures of the industry at large, in which brands are required to provide stable orders at prices that are sufficient to enable compliance with the standard.

These elements make our proposal a drastic departure from any existing "certification scheme" or any other program that has been proposed by the apparel industry.

16) Five years after campus codes of conduct were implemented, are we certain that campus' apparel is still being made under abusive conditions?

Among experts in the field, there is no doubt that most campus logo apparel is being made in sweatshops. Both the WRC and FLA acknowledge that logo goods are being produced in factories that routinely violate workers rights. One must only look at the public factory reports posted on the WRC website - http://www.workersrights.org/freports.asp - to confirm this reality.

It is not surprising, after five years of campus codes of conduct, that logo apparel is still being made in substandard conditions. First, it is important to recognize that conditions throughout the global apparel industry remain abysmal, and the subset of the industry that produces logo goods is not an exception. Indeed, as noted above, campus apparel is being produced in the same factories that produce for big box retailers like Wal-Mart and Target, and campus apparel is typically only a very small portion of each factory's production. Brands place tremendous pressure on factories to cut costs by forcing factories to compete - in a race-to-the-bottom - to offer the lowest bid. These pressures are the driving force behind sweatshop abuses and poverty wages. It is precisely because logo goods are scattered across so many factories operating under these pressures and because logo goods make up such a small portion of each factory's production that it has proven so difficult for our universities' enforcement agents to effectively monitor each of these thousands of factories and to bring to bear the necessary leverage to compel improvements.

Moreover, an additional key reason why conditions in factories that produce campus apparel remain poor is that licensees fail to reward factories that do respect worker rights. Complying with labor standards entails increased costs: it costs more to pay the minimum wage than to ignore it, and it costs more to buy necessary safety equipment than to avoid such purchases. Yet brands, including university licensees, rarely reward factories that take on the costs of respecting worker rights by taking into account these expenses when negotiating prices or by directing business to factories that standout for their compliance with labor standards. As a result, factories that do opt to accept the added costs of compliance become less likely to succeed than factories that violate workers' rights. Indeed, there are a number of factories that have made dramatic improvements in response to intervention from universities and the WRC, but which have closed or are in grave jeopardy of closing because university licensees have failed to reward these dramatic improvements with business. These include factories that have already closed, such as PT Dae Joo Leports in Indonesia, and factories that are in danger of closing, such as BJ&B in the Dominican Republic, Sinolink in Kenya, Lian Thai in Thailand, Mexmode in Mexico, and many others. USAS is circulating a list of such factories within the university community.

Given these realities - the scattering of a relatively small amount of university apparel across thousands of factories, punishing price pressure from licensees and other brands, and the failure to reward factories that do respect worker rights - it is not surprising that campus apparel is still being made in sweatshops. Our proposal is designed specifically to address each of these problems.

17) Aren't some elements of the proposed policy illegal?

We have no reason to believe that any element of the policy we are proposing violates any law. There are two areas in which we have heard general concerns raised.

The first concern is that the requirement that university logo goods be produced in factories where workers are represented by a union or other representative body could be illegal, specifically on the ground that such a policy would be preempted by federal labor legislation. We have received legal advice on this question from Mark Barenberg, Professor of Law at Columbia University, a widely recognized expert on domestic and international labor law and trade law. According to Professor Barenberg, the policy proposed passes legal muster in this area. "Private universities can implement the proposed policy, without raising any legal questions at all under federal labor law. As to public universities, the proposed policy again raises no federal labor-law questions when the policy is applied to supplier factories in foreign countries. If public universities apply the proposed policy to supplier factories in the United States, a legal question does arise, and opponents may attempt to challenge this aspect of the policy. The question is whether such action is rendered illegal on the ground that it is preempted by federal labor legislation." In this narrow area concerning unionized facilities in the United States, "while USAS's proposed policy may face legal challenge, there are strong legal arguments in support of the policy, and the policy will, in all probability, survive the challenge." Indeed, according to a ruling by the Second Circuit Court of Appeals, states and cities may choose to buy goods only from unionized suppliers, without running afoul of the National Labor Relations Act. In sum, Professor Barenberg writes, "My conclusion is that the universities and their licensees may implement the proposed policy without incurring significant additional risk of violating federal labor laws." We are happy to provide Professor Barenberg's complete legal opinion letter upon request.

The second concern is that the policy could in some way violate anti-trust laws. As in the case of the union-preference issue, we have no reason to believe the policy raises legal problems with anti-trust rules. It is important to bear in mind that each time during the past decade that a new campus anti-sweatshop policy has been proposed, someone has objected that the policy will cause anti-trust problems. In every one of these cases - from disclosure of factory locations to wage disclosure - the anti-trust issue has turned out to be a red herring: no concern in this area has ever been borne out or even seriously posited. In the case of the new proposed policy, we are not in a position to respond to any specific concern about anti-trust issues because, to our knowledge, no one has yet made a concrete claim to the effect that any specific element of the proposal is illegal under anti-trust law. Instead, as during each previous debate about codes of conduct, general complaints about potential anti-trust violations have been raised without any specific arguments being made that could actually be tested by legal experts. The only area in which we can guess that serious objections may arise is the coordination among brands that would be necessary to implement the program. It is important to understand in this regard that brands already coordinate a great deal on code enforcement, including sharing information on supplier factories and, in some cases, actually coordinating how much production is placed in those factories (Gap and Limited Brands have a pilot program to do the latter). Another example: the U.S. government currently funds a program to develop a public database of factory audit information, which will be used by brands in their decisions about which suppliers to patronize. As far as we understand, there is nothing about these various types of coordination that violates anti-trust laws - if there is, the brands are apparently unaware of it. Indeed, in forums about corporate social responsibility, these approaches are touted by company representatives as "best practices". A legitimate anti-trust concern would only arise if it leads to brands colluding on prices - i.e. price-fixing. However, requiring that prices be sufficient to allow factories to pay a living wage and meet other code obligations does not require brands to collude. It simply requires that each brand, separately, make sure it is factoring the true costs of production into price negotiations with each supplier. Similar requirements are already included in California law and in the Department of Labor's apparel monitoring program, as discussed above in this document.

If anyone has any specific concern regarding anti-trust issues related to the proposal, we ask that he or she put forward these concerns, in detail, so that USAS can then respond.

Appendix

Source: Kauffman, Matthew and Lisa Chedekel. "As Colleges Profit, Sweatshops Worsen." Hartford Courant. December 12, 2004.